Why Democracy in Southeast Asia Will Worsen in 2023

2022 has not exactly been a banner year for democracy in Southeast Asia, which has regressed in the past two decades from an example of a democratizing developing region into one of extreme democratic regression (the only exception: tiny Timor-Leste). The Myanmar junta remains in power in that benighted country, overseeing a failed state. The junta has resorted to rising brutality and abandoned all pretense of interest in global opinion by jailing a former UK ambassador, executing four activists, and handing Aung San Suu Kyi a long prison and hard labor sentence. Former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte continued to oversee a crackdown on the media and civil society, as well as a brutal drug war, until the end of his term in June 2022. Thailand’s pro-military parliamentary coalition remains in power because of a flawed 2019 election, the banning of opposition parties, and the fact that Thai judges are beholden to the military and its allies. The Thai king, who is supposed to stay above politics, increasingly involves himself in both politics and business, and has expressed some interest in returning the country to an absolute monarchy. Cambodia has cracked down on a broad range of opposition activists. Malaysia, while jailing former prime minister Najib tun Razak for his crimes—an important step towards curbing impunity—retains a ruling coalition dominated by Najib's party, which ruled Malaysia autocratically for decades. In Indonesia, President Joko Widodo (popularly known as Jokowi) has done little as the military accrues power and rights are curtailed for LGBTQ+ citizens and others.

But 2023 is likely to be worse for democracy in Southeast Asia. Jokowi will increasingly become a lame duck, and Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto, who has signaled his disdain for democracy and desire to rule as a strongman, has accepted his party's nomination to run for president in 2024. With Jokowi term-limited, Prabowo will be a strong candidate; he is already amassing allies and endorsements from other key political players in the country.

More on:

Prabowo also has a terrible rights record from his tenure as head of Indonesian special forces in the Suharto era. He was banned from obtaining a U.S. visa for years for his alleged role in the killings of rights activists and other crimes during the bloodshed in East Timor, then a province of Indonesia (in the waning days of the Trump administration, the U.S. granted Prabowo a visa to visit Washington after he became defense minister).

With Prabowo as president, Indonesia could easily lose its status, along with Timor-Leste, as one of the few still-solid democracies in the region. Indeed, Prabowo has already suggested he sees little value in democracy. If he were to win the presidency, he could cancel the many local and regional elections that have become the lifeblood of Indonesia's highly successful program of democratic decentralization to consolidate power in himself and a small circle of advisors.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, there is little evidence that the new president Ferdinand Marcos Jr will be any more democratic than Duterte. He has continued Duterte's crackdown on the media and civil society—prominent activist Walden Bello was arrested shortly after Marcos Jr's inauguration—and is protecting Duterte from any investigations into the former president's massive rights abuses. Prominent opposition leader Senator Leila de Lima remains in jail.

In Thailand, another major Southeast Asian state, elections must be held in 2023. The population has likely tired of the government, led by a military-aligned party that has been in power since 2019 through unfair elections (following a military coup in 2014, those same leaders also ran the country for five years under intense repression). In all likelihood, Thais will vote in large numbers for opposition, pro-democracy parties, but these parties will be prevented from taking office, as the pro-military parties and their allies maneuver to keep the opposition out of power.

Malaysia also must hold general elections in 2023, and there will be plenty of maneuvering, horse-trading, and other shenanigans in advance of the elections. Although new parties will be contesting, it seems highly possible that UMNO, the party that has dominated the country, often by employing semi-autocratic means and staggering gerrymandering, will win. The economy has been relatively strong, the opposition is fractured, and UMNO and its allies seem in strong shape to win.

More on:

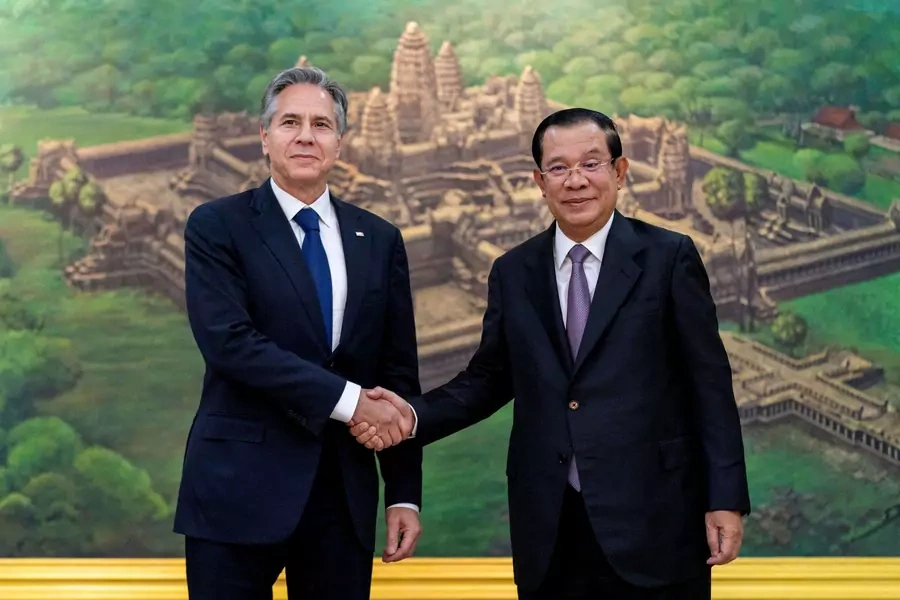

In smaller regional countries, the situation does not look much better. Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen, who has ruled for three decades, will likely heighten his campaign against the remaining semi-free press and civil society even further, as he maneuvers to eventually install his son, Hun Manet, as his successor. Vietnam also continues in a more authoritarian direction. While debt crises and economic problems have caused some ferment in Laos, this highly unusual protest is unlikely to have much impact on the ruling regime, which remains in full control of the country and represses even the slightest demonstrations.

Myanmar will likely continue to descend into ever-more-brutal conflict, including in major urban areas. The ruling junta may be losing ground to anti-government guerillas and ethnic armed organizations, but dislodging the military regime, even if it happens, will take time—and leave an unsure future for the country.

In sum, 2023 promises to be another horrible year for democracy in Southeast Asia. There are potential bright spots—perhaps the pro-democracy opposition will win in Thailand and their victory will be respected, or perhaps there will be real progress in Myanmar—but overall, the outlook is grim.

Online Store

Online Store